Navigating the education moral maze

- Teaching And Learning

Navigating the education moral maze

The final report of the Ethical Leadership Commission is a noteworthy and welcome publication. It highlights the challenges we face in balancing ethical decision making with the demands of accountability and the competing pressures magnified by financial uncertainty in schools. The impact of test-based accountability on both the teaching profession and our pupils has been significant. Only now are we looking back to view the damage caused. This includes the normalisation of test score inflation; our obsession with outcomes; narrowing curriculum priorities, driven by anxiety to ensure pupils cross the magical lines of good progress or standards met – sometimes unethically – and performance management processes based on crude numerical targets.

Thankfully, there is growing acceptance that when we give priority to a measurement in order to determine education policy or decision making, the more susceptible the system becomes to corruption. It underlines that target driven improvement often falters through failure to understand schools are essentially complex, adaptive organisations. The illusion that schools improve linear fashion simply by mandating an outcome target is a misguided ideal which distorts the reality of what schools reallydo to improve.

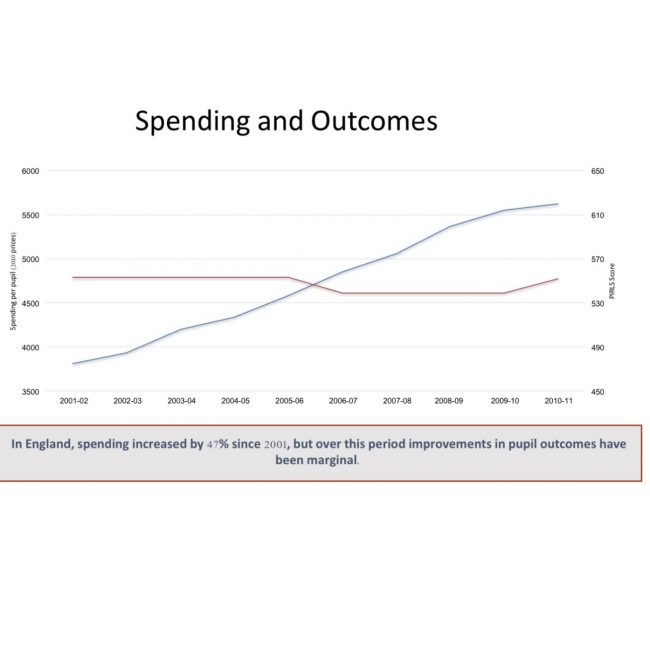

Take the national strategies developed to raise standards in maths and English between 1997-2011. Millions of pounds spent developing resources in how to teach phonics, grammar and basic maths skills through mass produced lesson plans, schemes and frameworks. Teaching was evaluated using stop clocks monitoring how long was spent delivering mental oral starters or whole class reading comprehension tasks. Teachers became ‘milkmen’ – deliverers of nationally defined curriculum statements. We taught to a testing standard rather than to students’ learning needs. Curriculum coverage became the focus rather than depth or quality of learning. Number fans and instructional grammar prompts decorated classrooms. If you didn’t use a counting stick in a maths lesson, your teaching was questioned. The resources became more important than the relationships. The result? We saw the biggest increase in education spending in our recent history with a minimal impact on pupil outcomes. (See table below)

In the years preceding the National Strategies, our education values steadily eroded. Pupils became products, teaching viewed as a transaction; we valued the measurement of tests, more than the deep experiences of learning. Good teachers became defined by targets achieved rather than the meaningful connections students make between learning and the world. In other words, high stakes testing and accountability corrupted what our pupils most needed, often resulting in poorer outcomes for those students in greatest need of a balanced, rich and diverse education.

By contrast, in an era of networks, it is the power of the group to make a collective difference that becomes most significant. The traditional script of school improvement tells a narrative of dashboards, target setting and compliance frameworks, the network provides a model for organic learning and organisational growth which is driven by practitioners defining what matters most within their context. It is the latter which provides a maturity model for sustainable school improvement that is bottom up, rather than top down. In networks, we learn differently:

- the portability of communication through technology facilitates learning between networks rapidly

- relationships and connectivity build discretionary effort between and beyond schools

- the reality of fiscal, pressures and diminishing local government resources pull us closer together to find solutions to common problems

- we are more equal as schools now than we ever where – not withstanding big challenges in specific regions

- the focus is on trust and not test based accountability

In other words, compliance and accountability frameworks are blunt instruments in an increasingly complex and sensitive education landscape.

An example of trust-based accountability is the Getting Ahead London coaching programme. Commissioned by the Greater London Authority (GLA) and first undertaken in 2017 it has had a transformational impact, not only on creating a more sustainable leadership pipeline but also in highlighting how moral capital underpins collective learning. The GAL programme targeted sixty aspiring headteachers from senior leaders across London schools. This initiative came as a key recommendation of the 2015 Building the Leadership Pool in London School, which highlighted our need tomeet the duel challenge of both retaining our best school leaders and creating a headteacher recruitment succession planning strategy. The GLA’s vision for the programme was:

“To establish a world class system for identifying and nurturing future headteachers in order to ensure London has a strong supply of outstanding school leaders.”

Comprising of three main elements, the programme focused on a collaborative model of learning where attitudes, confidence and opportunity were prioritised as much as knowledge and skills. At the core was a focus on group coaching in trios where carefully selected, trained headteachers worked with aspirant heads to explore elements of leadership in a fail-safe, growth orientated space. The programme also gave participants opportunities to shadow headteachers in real time, focusing on mutually agreed aspects of leadership practice – formative assessment for future leaders. The shadowing was tailored to individual needs, exploring specific elements of leadership, often overlooked in preference of the perceived leadership strategies. Alongside this, participants and coaches were able to build social networks that deepened the learning experience for everyone. These included planned networking events, master classes and opportunities to engage in debates with serving headteachers. It provides a very different narrative to about how best we learn.

What the programme demonstrates is the significant value of being able to learn from one-another in a social exchange – its all about collaboration, sharing and learning together – the network. The value of connectivity is often underplayed, or given less status as a tool for learning than acquisition of knowledge. As we see time and again, the value given to learning as a social construct necessitates we value the rehearsal more than we do the final performance. Networks flip the theory that our potential for growth is restricted by access to knowledge or set skills. Within the network, we are equal; we all have as much to contribute and learn from each other. As one programme participant commented:

“This programme has affirmed my enthusiasm and desire to become a headteacher. It has made me believe I can be who I really am and still be a headteacher. I will be acting headteacher three days a week from next term and I now feel confident to do that; before I would have been panicking. Now I’m thinking ‘bring it on!’

Learning is a social activity and has the greatest potential to flourish when it is co-constructed with others’ participation, engagement and common ownership of problems. An ethical, relational approach to leading schools is also strengthening teacher agency between what we do and why we do it. Outcomes matter but should never be used to define the work of teachers per se. The real worth of teachers’ work can be found in the behaviours and exchanges we adopt through learning centred relationships. Moral purpose becomes tangible only through the quality of interaction we find in our schools. This not only models ethical professional learning but also reinforce to students that they are worth much more than a grade.

)